GIS is increasingly being seen as much as a place to think as a simple data management and mapping tool

Gillings & Goodrick (1996) “Sensuous and reflexive GIS: exploring visualisation and VRML”

I’m very grateful to have been allowed to sit in on a GIS course this semester with students from the Archaeology department. Whilst the material is obviously therefore focussed on archaeological subjects, and I’m still very much at the beginner stage, it’s easy to see how this could be applied to some wonderful things in history at large.

For the uninitiated, Geographical Information Systems are essentially software to create and work with maps. Here is not the place to go into technicalities, suffice to say that – theoretical and practical limitations, not to mention the standard historical source criticism notwithstanding – you can use a program like ArcGIS to view different sorts of maps, to query them against each other like in a database, and to create your own maps as a result.

This is essentially my idea of heaven. Of all the theoretical constructs I’ll be grappling with over the course of my PhD, the most important one will be to ensure I can argue a case for playing with maps. I’m all for incorporating the experience of space and place into my research (I’m pretty sure this is the most fundamental way that we understand the world), and spatial history has been quite a topic of conversation in recent years. I get the impression, however, that GIS itself has been associated with a scientific/positivist mindset that is ill-suited to historical research; I’d like to get under the skin of that, because I am convinced that tools like this need not even focus on quantifying data, let alone steer the historian into dull, empirical thinking.

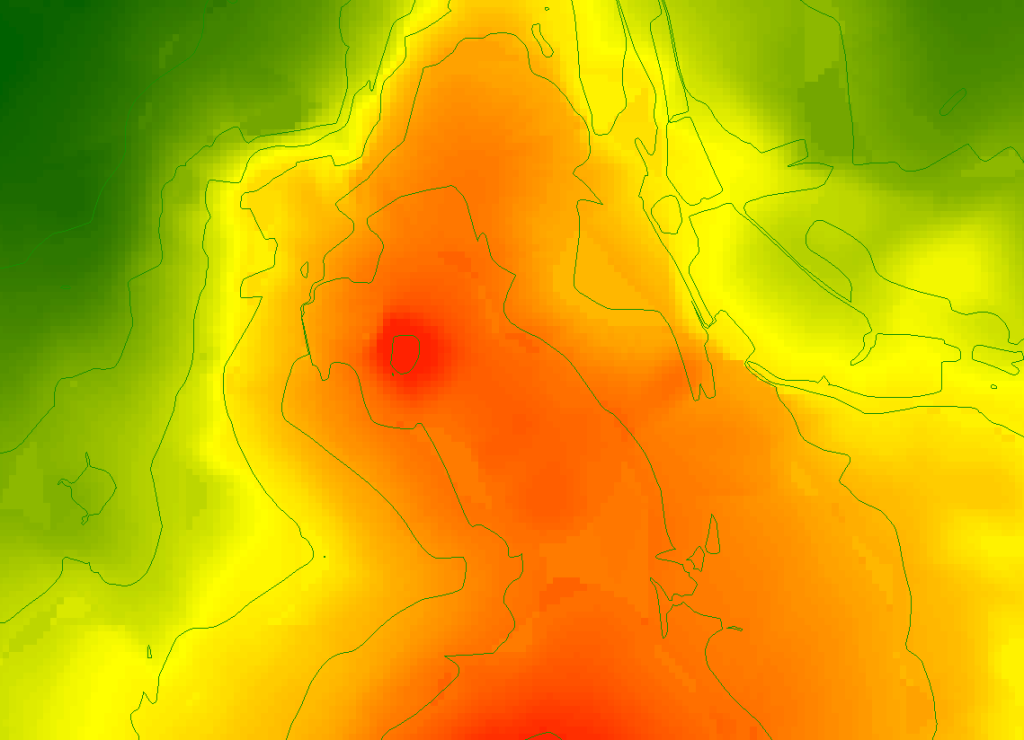

Data from EDINA.

First things first, I’ll point you at EDINA, an incredible source of both current and contemporary digital maps. Access is restricted to those at certain institutions sadly, but if you can get in it’s a wonderful thing. This map is of present-day Wolverhampton city centre, and is fairly easy to read. I’ve superimposed 5m contour lines – you can see for starters how St Peter’s is at the very pinnacle of the town; and also what an impact the earthworks of the ring road have had on the topography of the area.

But contours are not very easy to get a sense of; we have a more sophisticated version available here, colour-codable to ones heart’s content. Below are two maps showing different styles of elevation data of the same area as above in Wolverhampton. You can see better here how Wolverhampton sits on a hill – if you were to zoom out you’d see that this is the far reaches of the ridge of hills running NW to SE across the Black Country. The second map shows even more clearly the changes in elevation – what’s particularly noticeable here is the human effect of topography. The ring road, canal and railway line are all very obvious.

The next step, for me at least, is to think about changes over time. The map below shows the first Ordnance Survey town plan of Wolverhampton in 1886, superimposed over the elevation map. Sadly there’s no major data source for historical elevation – although I hope to have a trick up my sleeve for this – but you can get an idea of the lie of the land in the north-western corner of town, as it falls away from the church. This starts to now become “phenomenological” data – that is, something that tells me about the experience of a place. For example – it’s clear that the lower land is to the East of town, and indeed we know that the bulk of Black Country industry was to the South and East of Wolverhampton. What does this mean then for, say, a miner living on Stafford Street? If nothing else, it tells me that his walk home is uphill – just what you want at the end of a heavy day.

You may of course wish to compare those streets to today’s. This one shows some of the challenges of representing geographical data over time – it can be extremely messy. But just look at the massive changes in this part of town. The ring road has blasted through, destroying the streets of 1886. The canal basin is now just a stub but previously carried on to the side of Southampton Street – which is barely there anymore. And all the courts and alleys on the West side of Stafford Street? Now home to Wolverhampton University.

If you’re eagle-eyed, you’ll have spotted the empty spaces on the 1886 map. These are brand new streets (Whitmore and Thornley), yet to be built up with the housing that still stands today. This is because they were the result of a slum clearance scheme in the early 1880s – so what was there before? We have to trace back for this.

What have I learnt from superimposing scanned old maps? It’s hard, really hard to get right. I’m not in the position yet to be able to do accurate comparisons between individual plots of land; however, we can get an overview of early modern Wolverhampton using Isaac Taylor’s famous map of 1750. This is, of course, pre-canal, pre-railway, and although from Taylor’s annotations it’s clear that industry and urbanism are key to understanding the town, this is very much the plan of a medieval town that has yet to transform itself. The colour-coding is the same – St Peter’s remains at the top of the hill where it had already stood for hundreds of years, a landmark in the region. It’s clear that Wolverhampton was situated on that last promontory of the Black Country ridge, overlooking the Smestow valley and Aldersley Gap on one side, and the undulating, proto-industrial Black Country on the other. Much as I didn’t like the messy previous map, I rather like this one -Taylor made something of a work of art here.

This gives me a starting point for a better understanding of the town. Any approach to the town would have kept St Peter’s in view; and much of the building follows the hillsides and avoids the valleys. Of course, that’s not always true – see Barn Street, better known now as Salop Street, which is starting to string out along the trade route to Bridgnorth. I wonder if there’s any significance that both of Wolverhampton’s major city fires broke out on Barn Street?

As you can tell, I’m very excited to learn GIS, but also to apply it sensitively and carefully to the history of actual people; individuals more so than aggregates, for whom experiences matter more than data.

READ

Brownhills Bob has loads of map-based studies of his part of the Black Country; and the Black Country Historic Landscape Characterisation is a wonderful resource for local historians interested in map studies.

Leave a comment